John Eielson McCartney

|

December 30, 1953 - September 25, 2018 |

|

Life is good. Anyone acquainted with John McCartney longer than 15 minutes knows that was his cheerful mantra, one he repeated as recently as the day before he died. John Eielson McCartney, 64, of Seattle, passed away Tuesday, Sept. 25, 2018, after an apparent stroke while walking home from a neighborhood grocery store. On July 3, John was hospitalized for several weeks after collapsing and cracking his skull; within a few days he suffered cardiac arrest and then a stroke. Family, friends and co-workers will remember him for his upbeat spirit, his sharp wit that frequently strayed to good-natured black humor, his passion for genealogy (he was proud to call California Gov. Jerry Brown a distant relative), his mischief and his quiet generosity. John also enjoyed trips abroad, and it could be said that kicked off with his birth in Alaska before it became the 49th American state.

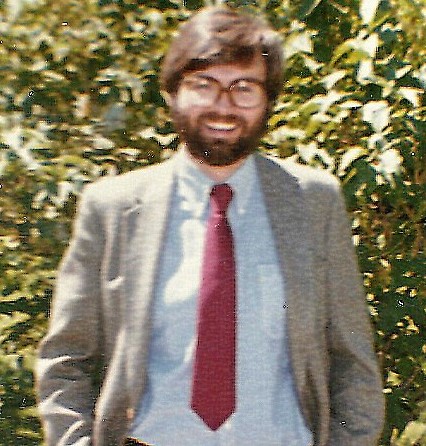

John was born in Fairbanks on Dec. 30, 1953, to Truman and Dorothy McCartney, just hours after the couple were in a car accident. His father was a civil service employee at Eielson Air Force Base, hence John’s middle name. The family moved to Bermuda when Truman was transferred there, and John attended kindergarten and first grade. The family was again moved, to Wheelus Air Base in Tripoli, Libya, where they lived for eight years, until they were evacuated because of the Six-Day War in the Mideast in 1967. The family moved to Mountain Home, Idaho, where John finished his schooling. Upon his father’s retirement, the family moved — for the final time — to Bellingham, Washington. When he was 17, he met John Watkins, who would become his lifelong best friend, shortly after John McCartney’s three weeks in the Navy. Recognizing John’s intelligence, the Navy had him down for training in running nuclear powerplants in ships and submarines. But sleep deprivation quickly took a toll and he was granted an honorable discharge for medical reasons. John Watkins ran into him on the campus of Western Washington University, where John McCartney apparently decided to hang out because that was the place with the greatest concentration of people his age. John McCartney has said that he realized that if he went to college then the party could continue for another four or so years. He attended Skagit Valley College in Mount Vernon, where he was on the Dean’s list every quarter. After earning an AA degree in communications, he enrolled in Western Washington University in Bellingham, where he earned a degree in journalism.

Both John McCartney and Watkins hitchhiked to Mountain Home one summer. “It was on this trip that I developed the theory that no one will pick you up hitching unless they figure they are a bigger threat to society than you are,” John Watkins said. “One of our rides was a very careful driver in a very nondescript car who eventually revealed that he was a heroin dealer from Manhattan, Kansas. Apparently the stuff in the trunk was why he was such a careful driver.” Getting through Yellowstone National Park was tough. “Most of the cars going into the park were full of families with young kids, exactly the sort of people who don’t pick up hitchers,” John Watkins said “One guy got a flat … so I walked over and asked if I could help. He resolutely did not look at me or give any indication I was there.” That’s when John McCartney started singing part of “Riders of the Storm,” a song by The Doors: “There’s a killer on the road/His brain is squirming like a toad … If you give this man a ride/Sweet family will die/Killer on the road.” “He was probably right in thinking there was no chance that guy would ever acknowledge our existence,” John Watkins said. “John’s humor and sense of mischief could offend some people, but behind it was an intelligent and thoughtful man who was a good judge of people.” When John McCartney got out of college, he worked in public relations for St. Joseph and for St. Luke’s hospitals in Bellingham, saving money for a bicycle tour of Europe. Those travels led him to Israel, where in 1981 he volunteered on kibbutz Kfar Giladi. He spoke fondly of his time there, except he hated harvesting chickens.

Back in Bellingham, he was ready for a change in scenery and looked at a map of the U.S. Texas caught his eye and he started humming Dean Martin’s song “Houston.” It turned into a plan, and he bought a motorcycle and headed south in 1982. The bike broke down in Odessa, Texas, so he got a bed at the Big Tex Bunkhouse and a job as a short-order cook. He soon landed a job as a health reporter at the Odessa American. He was moved from reporting to the news desk, where he found a home and a career. He excelled at page design, earning a front-page award in statewide competition, and at handling nation and world news, for which his knowledge of foreign countries, their histories and politics served him well. He eventually developed an affection for writer Jacqueline “Jackie” Toller, but at the time he wanted to act on it, she was dating another writer. “I knew that wasn’t going to last long,” he has said, and he was right. One evening at a nightclub, the man she had dated was sitting at one side and coincidentally Jackie and some work friends were on the other. John has said that when he arrived, he sat down to chat with the man, who spoke of Jackie in a disparaging manner. John said he listened, thinking the whole time, “OK, she’s available.” He lost no time, coming to join Jackie and friends and hitting on her, including wrapping her in a half-hug, despite her efforts to cordially blow him off. He held her tight as they danced to “Free Bird,” and they went for a motorcycle ride. They began dating, and their fates forever intertwined. In 1984, John got a job on the news desk at the Billings Gazette in Montana to be closer to his family in Bellingham, and was devastated when his father died a few weeks before he planned to move.

He started missing Jackie, and called her in January 1985 — at 4 a.m. — to invite her to come to Montana. The calls came in quick succession after she kept angrily hanging up on him. Later in the day, she accepted his offer. John and Jackie were married Sept. 30, 1985. While in Montana, the couple went to Yellowstone National Park 13 times and took an occasional trip to Canadian provinces Alberta and British Columbia. They moved in 1988 to Port Angeles, Washington, when John got a job as news desk chief at the Peninsula Daily News. He eventually became the newsroom’s managing editor, and circulation grew every year he was in that position. He and Jackie amicably separated in 1995, and John put off the divorce so she could stay on his health insurance until hers kicked in at the now-defunct Kent newspaper. Jackie said if she’d let him, he would have given her everything they owned. The pair remained close and occasionally visited each other, especially when John left the Port Angeles paper and got a job in 1997 as assistant city editor at the Bellingham Herald. He accepted a job as editor for national and world news at The Daily Herald in Everett in 1998, a job he would hold until his death. He lived in Everett a while before moving to Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood. He was a volunteer at the Center for Wooden Boats and the Seattle International Film Festival.

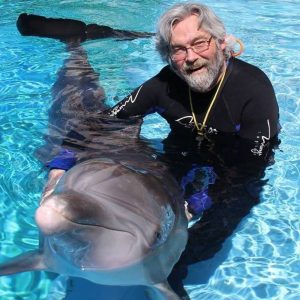

He was instrumental in getting Jackie McCartney a job at the Everett paper, and in 2017, when she was in Texas, he invited her to move in with him because he was concerned about her health and finances. She said that within days he began calling her by the pet names he invented while dating and married: “Bear,” “Boo,” “Wee One,” “Little Britches.” She was startled when he used her actual name. A few weeks before he passed away, they became engaged to remarry. “I haven’t seen his face light up with such a huge smile out of sheer happiness in maybe ever,” Jackie said. As John grew older and his hair turned silver, he was periodically mistaken for George Lucas by fans who wanted autographs and selfies. He said he saw some similarities in the hair and beard between him and the filmmaker who gave the world “Star Wars,” but didn’t understand the constant misunderstanding. True to form, however, John was amused. “So I’m waiting at a bus stop in Wallingford,” John posted on Facebook, “when a fellow leans way out of his car with a camera and says, “Gotcha on camera George Lucas!”

John was a frequent donor to the Red Cross and the Salvation Army in times of national or international disasters. Aside from his generosity toward his ex-wife, he took John Watkins — who owns the used-book store Twice Sold Tales in Ballard — out to dinner on his day off so John Watkins could get at least one good meal in him that week. He donated some of his vacation days to fellow employees who needed help but had run out of PTO for the year. His extensive genealogy work led him to discover some relatives in Indiana with unmarked graves. John bought a plaque for one and regretted that he couldn’t afford to buy others. His world as he knew it came crashing down on July 3 when he passed out in an Everett grocery store on the way to work. As he later put it, “a series of unfortunate events” began with a seizure after being taken to a hospital, where he was admitted. On July 5, he went into cardiac arrest for about six minutes, and at some point in the next couple of days he suffered a large stroke. He defied doctors’ expectations, however, and continued to improve. After a short program of acute rehabilitation, he came home Aug. 10. Toward mid-September, chafing at restrictions such as having to sometimes use a walker and his inability to safely drive, missing his workplace, frustration with some short-term memory loss and dreading medical bills, he fell into a deep depression, common among stroke survivors. Seeing a new primary-care doctor offered hope and he spent the weekend before he died fiddling around with financial accounts and figuring out a way he and Jackie could have enough of an income on which to live and to keep paying the bills. “Life is good,” he said Monday after he finalized those plans. John was back to feeling confident about the present and the future, his laughter returned as did the jokes. Late morning on the day he died, their cat was winding around Jackie’s feet and purring, and she remarked that the cat was sucking up to her for breakfast. A bit later, John started stroking her arm, and grinned when she looked at him. “What are you doing?” she asked. “Sucking up to you for breakfast,” he said. It worked for the cat. Late that afternoon, he left to walk to the store. He stopped at the men’s room at a nearby park, and a witness said he fell to the floor. Police said paramedics worked on him for half an hour but he could not be revived. A medical examiner’s report indicates John suffered another stroke. He was preceded in death by his parents; a sister, Leone Moena; and two nephews, his sister Babs Kobersteen’s children, Rick Wheeler and Rodney Wheeler. Survivors include Babs; niece Kacy Sigl, Babs’ daughter, and husband Ralf Sigl; nephew Keith Moena; great-nephews Oscar Sigl and Sam Sigl; fiancé Jacqueline McCartney; and best friend John Watkins. John was cremated, and plans are to bury his remains at Oak Hill Cemetery in Red Bluff, California, where many ancestors are laid to rest. A celebration of life is planned for 1 p.m. Oct. 20 at The Daily Herald, 1800 41st St., Suite 300, in Everett | |